The UN World Food Programme announced just last week that over a quarter of a billion people around the globe could suffer acute hunger by end of this year in large part owing to the coronavirus crisis — a doubling of the 130 million people estimated to experience severe food shortages last year.

Such forecast makes all the more notable the three-way split screen that has been flickering in the news recently across the United States — showcasing barren shelves at grocery stores, miles of cars and people lined up at food banks, and milk by the millions of gallons being dumped in Wisconsin and Ohio as well as tons of fresh vegetables being plowed back into the soil in Idaho and Florida.

As jarringly incongruous and disturbing such split-screen images are, they have helped bring into stark relief the surprisingly sclerotic rigidity of the U.S. food supply chain amid the prodigious disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

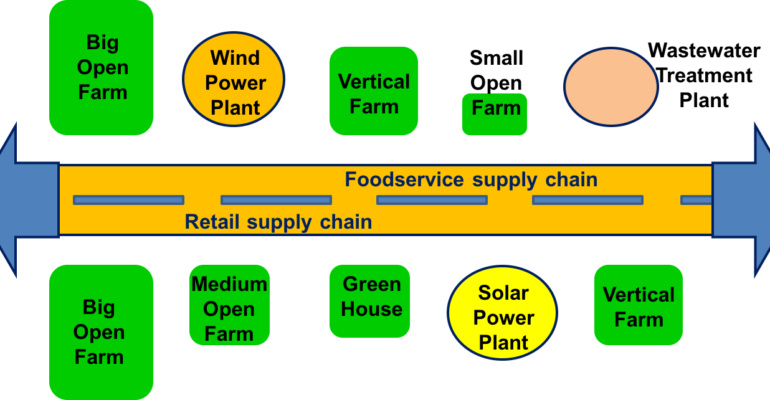

At the heart of America’s fresh-produce supply-chain predicament in the time of Covid-19 are the double strands that make up this supply chain — running in parallel and perhaps even looping around each other, but never quite meeting and converging.

One supply-chain strand supplies the foodservice channels of restaurants, schools, hotels, offices and coffee shops, while the second strand supplies the retail channels of grocery stores, supermarkets and other retail outlets.

Never do these two fresh-produce supply-chain strands converge in normal times, but remain distinctly discrete and resolutely independent of one other.

And this explains how when Covid-19 shuttered in quick succession myriads of restaurants, schools and coffee shops across the country, the producers and the roughly 15,000 suppliers that cater to the $300-billion U.S. foodservice industry are suddenly unable to sell the bulk of their produce.

And in attempting to pivot from the foodservice supply chain to the retail supply chain, they find themselves confronted, not only with the time-consuming and costly repackaging and relabeling requirements for their produce, but also with the daunting task under time duress of finding proper contacts as well as developing the needed contracts to deliver and sell their produce through the retail supply chain instead.

With many producers and foodservice suppliers completely unprepared and ill-equipped to accomplish the foregoing, many are forced to make the final dreadful choice of destroying millions of pounds of fresh food that they can no longer sell.

The industry trade group Produce Marketing Association estimates that approximately $5-billion worth of fresh fruits and vegetables have already gone to waste in the United States.

Thus, redesigning America’s fresh-produce supply chain post Covid-19 to make it certainly more nimble and flexible in routing and rerouting as needed the logistical paths that connect from which farms to which tables is absolutely imperative.

Equally imperative in such redesign is also to make the fresh-produce supply chain definitively more inclusive and sustainable.

Here are six essential touchstones that should inform the much-needed re-engineering of America’s double-stranded fresh-produce supply chain after Covid-19.

(1) Regionally and locally-based— greater geographical proximity between the re-engineered supply-chain sources (producers) and sinks (retailers and foodservice providers) fosters increased resilience in terms of shorter distance, quicker access to produce, and allowing for time to repackage and relabel produce in events where there is need to switch supply-chain strands; proximity also promotes sustainability in terms of shorter food miles, lower concomitant greenhouse-gas emissions, less food waste during transport as well as greater produce quality and freshness;

(2) Inclusion of small and medium-scale producers— Addition of medium and small-scale producers in the re-engineered supply chain not only promotes economic inclusivity but fortifies the supply chain’s resilience given the relative ability of medium and small-scale producers to react more quickly and nimbly to projected changes in demands in the supply-chain sinks;

(3) Mixing of foodservice and retail clients in the chains— Combining to the extent possible foodservice and retail sinks in the re-engineered supply chains fosters resilience in regard to establishing and maintaining clients in both strands of the supply chain, and thus providing greater facility in events where produce needs rerouting from one supply-chain strand to the other.

(4) Inclusion of indoor and/or vertical farm producers— Addition of indoor and/or vertical farms significantly boosts the resilience of the re-engineered supply chain in terms of increased supply reliability (independent of weather, season, climate and geography), higher produce yield and quality, increased food safety owing to cleaner and controlled-environment operations, and amenability to the automation of operations for labor efficiency. The recent decision by Wendy’s, for instance, to source all of its tomatoes for all of its 6,000 restaurants across North America from indoor hydroponic greenhouses has helped enable the American fast-food company to uphold its motto of Always Freshby way of ensured quality as well as enhanced food safety, predictability, reliability and product traceability for its now far more dependable fresh-tomato supply chain;

(5) Linking producer farms with sources of renewable energy— Incentivizing and linking producer farms to ready sources of renewable energy, including solar and wind power plants, promotes enhanced environmental sustainability. Especially in temperate regions with reduced solar irradiance in certain periods of the year, producer farms may also be linked with wastewater treatment plants that generate renewable natural gas from digested organic wastes as exemplified by the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant in Brooklyn, New York City; and,

(6) Certification of the supply chain nexus— Certification for resilience, inclusiveness and sustainability (that is, a RISe certification) adjudicated and awarded by an independent body to supply-chain nexus of producers, suppliers and retail/foodservice clients would be a great boon to the fresh-produce distribution industry as well as to consumers, the general public and the environment.

With Covid-19 temporarily decimating the global economy and in the process exposing the vulnerability of partial paralysis of the American fresh-produce supply chain amid the chaotic disruptions wrought by the pandemic, a silver lining that has emerged is that America’s fresh-produce supply chain can very well be re-engineered for a much-needed upgrade — toward greater resilience, inclusiveness and sustainability.

_______________________________

Dr. Joel L. Cuello is Vice-Chair of the Association for Vertical Farming (AVF) and Professor of Biosystems Engineering at The University of Arizona. In addition to conducting research and designs on vertical farming and cell-based bioreactors, he also teaches “Integrated Engineered Solutions in the Food-Water-Energy Nexus” and “Globalization, Sustainability & Innovation”. Email cuelloj@arizona.edu.

Comments are closed.